TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART XI: THE REPORT

Truman received To Secure These Rights, the committee’s report, on October 29, 1947.77 He may not have expected the far-ranging recommendations that emerged from his carefully balanced committee, but he did not flinch from endorsing them. Congratulating the panel members for doing “a good job … what I wanted you to do,” he hailed the report as “an American charter of human freedom in our time” and “a guide for action.” The president wanted the document to inspire “men of good will everywhere [who] are striving under great difficulty to create a worldwide moral order.” He pledged that the federal government would strive to protect individual freedom based on “equal freedom under just laws.”78

The text of the report spells out in detail the liberal vision for expansion of civil rights in the years after World War II. The report’s emphasis on the duty of the federal government to protect individuals from racial discrimination contained the basis of the liberal credo for decades to come. The report asserted that Washington “cannot afford to delay action until the most backward community has learned to prize civil liberty and has taken adequate steps to safeguard the rights of every one of its citizens.” Furthermore, liberals contended that rights belonged to individuals and not to groups. Accordingly, blacks were entitled to equal treatment and, like all Americans, they should “tolerate no restrictions upon the individual which depend upon irrelevant factors such as his race, his color, his religion, or the social position to which he is born.79 This conception of civil rights would last into the mid-1960s. At that time, in response to the persistence of racism, civil rights activists called for affirmative action to treat African Americans as a racial group rather than merely as individuals and to compensate them for the consequences of white supremacy.

Credit: TrumanLibrary.gov

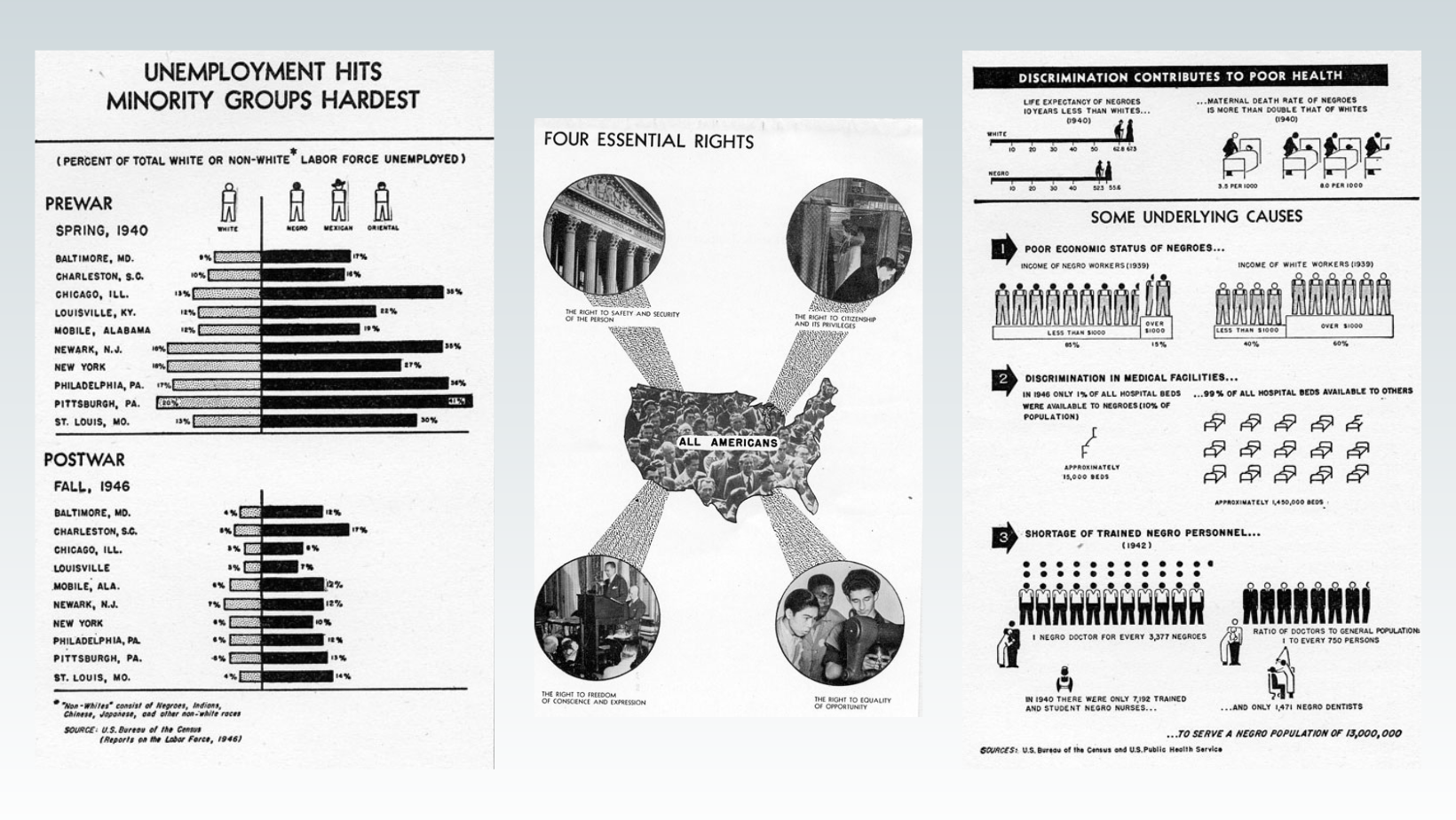

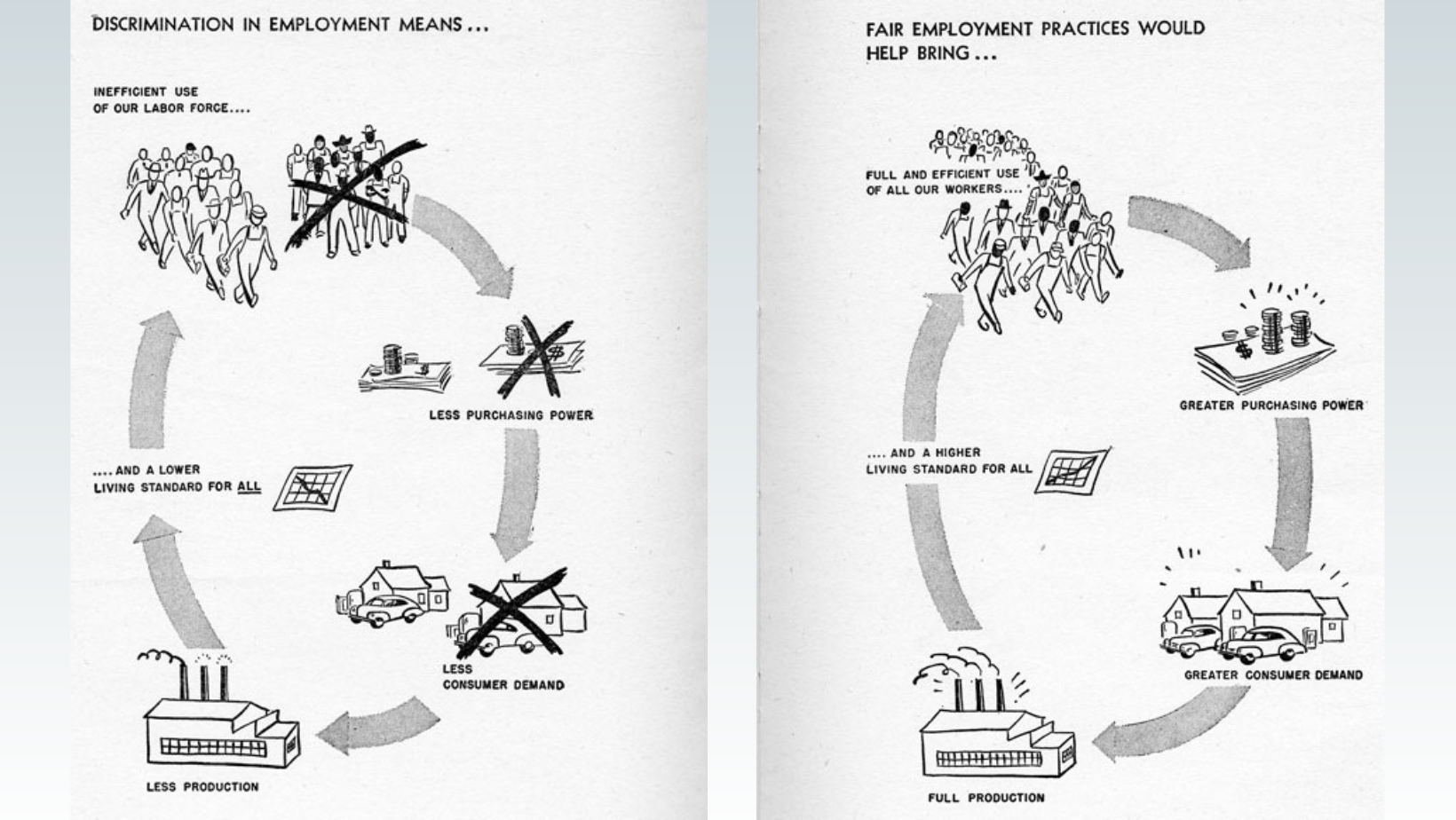

To Secure These Rights also reflected the liberal belief that bolstering civil rights stemmed from moral, diplomatic, and economic considerations. The report took a page from An American Dilemma by stating the PCCR’s faith *that the greatest hope for the future is the increasing awareness by more and more Americans of the gulf between our civil rights principles and our practices.’80 “The cold war heightened this awareness. In the struggle against the Soviet Union, the United States could not afford to tolerate racial discrimination within its borders and expect the rest of the world to believe its political and economic systems were superior to those of its Communist adversary. The report also catalogued ways in which racial prejudice hampered growth of the American economy. Bias cost the economy money in markets that were closed to black consumers, in the depression of minority wages, in higher expenditures to operate segregated facilities, and in reduced production that resulted from restricted markets and a reduction of purchasing power. Furthermore, the economy lost millions of dollars from racial disturbances.81

Credit: TrumanLibrary.gov

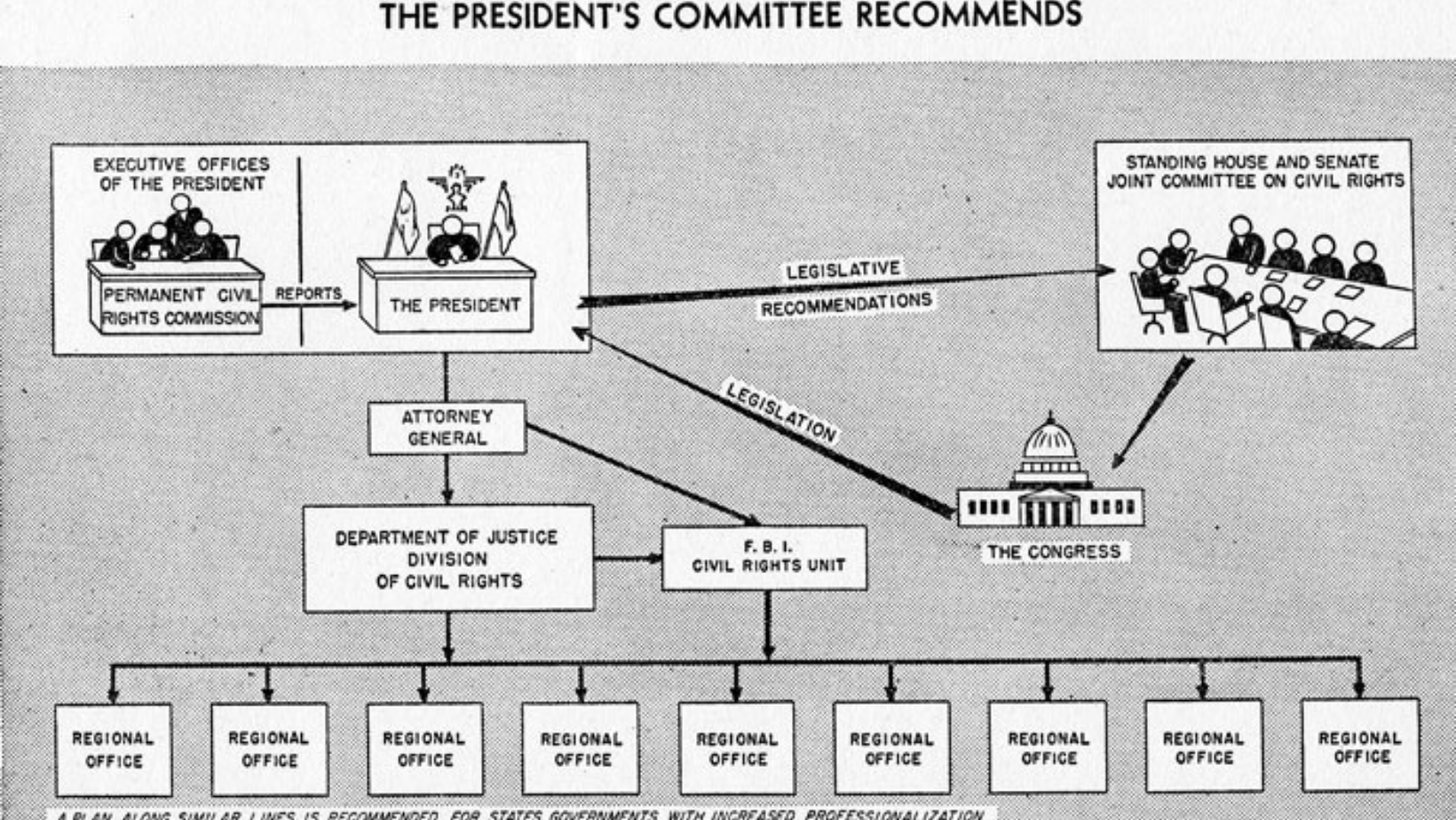

The thirty-four recommendations that appear in the report established the agenda for civil rights reforms for a generation to come. In addition to attacking disfranchisement and advocating the strengthening of federal law enforcement machinery against racial crimes such as lynching, the document proposed to dismantle segregation throughout American society. It condemned racial separation in housing, interstate transportation, public accommodations, the military, and employment. Most remarkable of all was the stand it took against school segregation. In challenging Jim Crow, the PCCR took aim at the ideology of white supremacy itself. “The separate but equal doctrine,” the report chided, “is inconsistent with the fundamental equalitarianism of the American way of life in that it marks groups with the brand of inferior status… There is no adequate defense of segregation.”82 Seven years later, in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court would reach the same conclusion in its historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

The report did not frame civil rights in merely legal terms, although it did emphasize them. Those who supported expansion of the suffrage, for example, did not view it as an end in itself. They expected newly enfranchised blacks and whites to join together and use their ballots to alter power relationships in the South and extend economic democracy to the most impoverished region in the country. However, in protecting the lives of minorities, the federal government would have to provide more than political and legal rights; it would have to improve opportunities for equal education and employment. The report addressed some of these issues by recommending laws to promote increased opportunities for African Americans in employment. education, housing, and health services.83

Credit: TrumanLibrary.gov

To Secure These Rights reflected and reinforced the larger movement for racial equality that was gaining strength in postwar America. In January 1947, a group of black Mississippians, many of them veterans, challenged the right of Senator Theodore Bilbo to take his seat in the new Eightieth Congress. Represented by the NAACP they charged that Bilbo had prevented blacks from voting by stirring up racial hatred and advising local officials to keep African Americans from casting their ballots. They achieved some success, as the Senate temporarily blocked Bilbo from taking his seat pending an investigation, and the conflict was resolved when the Mississippi senator soon died from cancer. In May 1947, another presidential commission released a report that called for an end to military segregation. In Clarendon County, South Carolina, blacks began a campaign to obtain buses from the local board of education to take their children to school, which the doctrine of “separate but equal” had yet to provide them. Their efforts culminated a few years later in a full-scale drive against segregated schools. A week before the PCCR issued its findings, the NAACP submitted a petition, drafted by W. E. B. Du Bois, to the United Nations asking its Commission on Human Rights to investigate racism in the United States. Although the U declined to interfere, largely at the U.S. delegation’s insistence, the petition demonstrated the increased militancy of African Americans and further publicized their grievances.84 Thus, the PCCR’s report converged with escalating attempts by African Americans on the local, national, and international levels to destroy Jim Crow.

PREVIOUS: Part X – The Committee Deliberates

NEXT: Part XII – Reactions to the Report

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes