TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART XIII: TRUMAN’S RESPONSE AND THE ELECTION OF 1948

Given the outburst from the South, Truman faced rough treatment in submitting civil rights proposals to Congress. The problem was not so much that conservative Republicans were in control of the Eightieth Congress, but that powerful southern Democrats could block attempts to pass legislation by undertaking a filibuster in the Senate, the graveyard of civil rights bills.

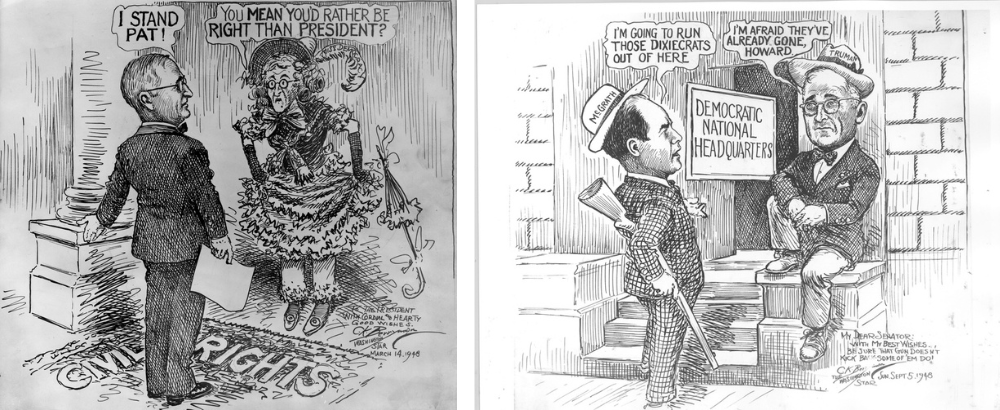

Truman was forced to spend a great deal of political capital to mobilize support for his program. With a cold war to fight at home and abroad, the president could not afford to antagonize southern lawmakers whose support he needed for these higher priority efforts. Accordingly, Truman devised a strategy to appeal to his civil rights backers without further alienating opponents. Looking ahead to running for president in 1948, the president and trusted political advisors such as Clark Clifford believed that he had to shore up his liberal New Deal base, including African Americans, by challenging Congress to enact proposals that he knew had no chance of passing. This strategy called for Truman to create a platform upon which to run for reelection and to blame the Republican leadership in Congress for failing to act on his proposals. His counselors guessed that although there would be a great deal of grumbling from southern segregationists, Dixie’s white Democrats would remain faithful to the party as they had since the Civil War.88

From February through July 1948, Truman and the southern Democrats engaged in a political dance: For every two steps forward the president moved, he took one step back. On February 2, he delivered a special message to Congress in which he proposed a ten-point program based on the PCCR’s findings. In addition to antilynching. anti-poll tax, and FEPC bills, the president called for ending segregation in interstate transportation, upgrading the Civil Rights Section into a division of the Justice Department, creating a Civil Rights Commission, establishing home rule and antidiscrimination measures for the District of Columbia, and adjudicating financial claims by Japanese Americans resulting from their wartime evacuation. The chief executive omitted the most politically incendiary features of To Secure These Rights: school desegregation and the ban on federal grants to segregated institutions. It did not matter, however, as Truman knew, because none of the measures, even the least controversial, had a chance of passing. Truman recorded in his diary: “I send the Congress a Civil Rights message. They will no doubt receive it … coldly. But it needs to be said.”89

Political cartoons by Clifford Berryman; courtesy U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

He proved correct. His bills never made it out of the Senate; nor did he fight particularly hard for them in the face of fierce southern opposition. Indeed, the president went to the Democratic National Convention in July prepared to accept a civil rights plank that wasn’t too offensive to the South and fell far short of his own program. However, again he shifted direction. Once Hubert H. Humphrey, a Democrat running for the Senate from Minnesota, engineered a liberal-labor coalition of delegates to replace the weak civil rights platform with a very strong one, Truman easily capitulated.90

Political events altered his game plan. The acceptance of the strong civil rights standard pushed representatives from Mississippi and Alabama to leave the convention and form the State’s Rights, or Dixie-crat, party, nominating Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for president and Governor Fielding Wright of Mississippi for vice president.91 Even more worrisome, on his left, Truman faced the Progressive party nominee, Henry Wallace, an original New Dealer who appealed to many in the liberal wing of the party and had support from the Communist party. In the South, Wallace campaigned before blacks and whites standing side by side and forcefully denounced disfranchisement and Jim Crow.92 Although there were still too few black voters in the South to make a difference, increasing numbers of African Americans in the North and West could affect the outcome of the election. These votes were not only up for grabs by Wallace, but also by the Republican candidate, Thomas E. Dewey, the reform governor of New York who spoke out in favor of civil rights.

Truman worried more about Dewey and Wallace than about Thurmond. To forestall any erosion of the northern black support he needed, the president responded in several ways. He called Congress into special session on July 26 to consider once again his civil rights proposals, which he knew were doomed from the beginning. No one doubted the political motivations behind this move. He sought to embarrass the Republicans, and in turn their party standard-bearer, Dewey, for failing to enact his proposals. He also engaged in red-baiting Wallace by accusing him of being a front man for the Communists.

Truman could not afford to depend solely on rhetoric, however, to shore up African American backing. For several months, A. Philip Randolph, who was no stranger to manipulating presidents, threatened to lead a mass civil disobedience movement of young black males against the cold war military draft unless Truman acted to eliminate segregation in the armed forces. Randolph’s demand took on greater weight because the president’s own civil rights committee had endorsed desegregation of the military. Like Roosevelt, Truman wanted to avoid a protest that would underscore America’s continuing racial discrimination and hurt the administration’s diplomatic efforts. Randolph’s gambit, backed by the new-found political strength of African Americans, worked. Truman issued two executive orders mandating the desegregation of the armed forces and the elimination of racial discrimination in federal government employment. Thus, Randolph completed what he had started six years earlier.93

At St. Louis Union Station, postmaster Bernard Dickmann (left) stands next to newly elected President Truman as he holds up the famous Chicago Tribune newspaper headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” (November 4, 1948). Courtesy Truman Library, photo 64-861

Truman’s calculations paid off. Only four southern states – Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, and Louisiana – defected to Thurmond. Thanks to Truman’s appeal to black voters, Wallace made a poor showing among them. Dewey’s lackluster campaigning and Truman’s claims that a Republican return to the White House would lead to another depression bolstered the president’s victory.94

PREVIOUS: Part XII – Reactions to the Report

NEXT: Part XIV – The Civil Rights Report and Truman’s Legacy

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes