TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART VI: CREATION OF THE PRESIDENT’S COMMITTEE ON CIVIL RIGHTS

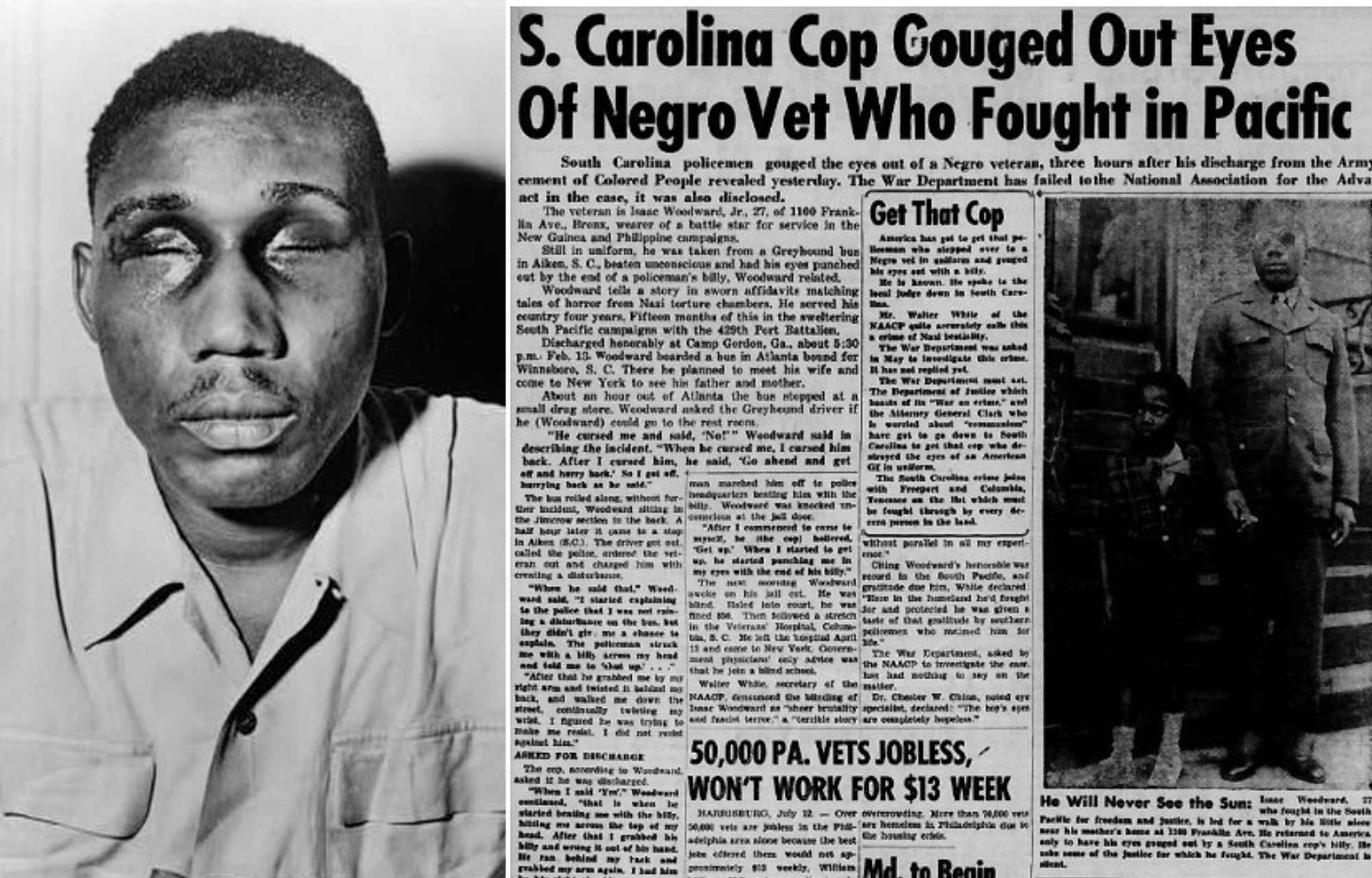

Truman was continually forced to balance his moral and political concerns because civil rights advocates applied concerted pressure on him to act. On September 19, 1946, in the wake of the Columbia riot, the vicious assault on Isaac Woodard, and the murders in Georgia and Louisiana, the coalition of organizations composing the National Emergency Committee Against Mob Violence met with the president at the White House. Led by representatives from the NAACP, the Urban League, the Federal Council of Churches, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and the CIO, the delegation reminded Truman that “Negro veterans of the late war for human freedom have been done to death or mutilated with a savagery unsurpassed even at Buchenwald.”29 Although the president was already aware of the postwar horrors in the South, he reportedly replied: “My God! I had no idea that it was as terrible as that! We’ve got to do something!”30

Photograph of WWII veteran Isaac Woodard with eyes swollen shut following assault and blinding. The photograph was distributed for a November 1946 speaking tour by Woodard and Thurgood Marshall. Courtesy Library of Congress

The solution that Truman devised combined moral outrage with political calculation. The idea to set up a national committee to reduce racial conflicts had been kicking around the White House since the outbreak of rioting in 1943. Nothing had come of it, but one of its proponents, David Niles, an assistant to Roosevelt and then Truman, revived the proposal during the meeting with the NECAMV. In consultation with Walter White, the NAACP’s executive secretary, Truman decided to create a committee through executive order rather than seek legislation that would be derailed by a Senate filibuster.31 In this way, the president accomplished a number of objectives: He satisfied civil rights advocates whose goals and methods he agreed with; he took political pressure off himself and transferred it to a committee; he avoided direct confrontation with southern Democratic lawmakers; and he established a forum to begin educating the public on the need to extend equality under the law.

Truman responded positively to the NECAMV because it reflected the kind of African American leadership with which he felt comfortable. In particular, the president found groups such as the NAACP and the Urban League responsible in presenting their case for equality. The National Urban League, founded in 1911, was almost as old as the NAACP and more conservative. Instead of protest, the league focused on negotiating with businesspeople and civic leaders to improve opportunities in black employment, housing, and welfare. Eleanor Roosevelt had worked closely with these organizations, and it was natural for Truman to cloak himself in his predecessor’s mantle as much as possible to enhance his political legitimacy. In contrast, he had far more difficulty dealing with more militant African American leaders. Four days after he met with the NECAMV, on September 23, the president sat down to confer with Paul Robeson, the gifted athlete, singer, and actor, and a delegation of representatives from the National Negro Congress, the SCHW, and the National Council of Negro Women. Robeson, the National Negro Congress, and the SCHW represented the left wing of the civil rights spectrum, and they had worked closely with Communists. The meeting proved a disaster, as delegates charged that lynching in the South was the moral equivalent of the crimes of Nazi war criminals then being prosecuted at the Nuremberg Trials. Truman somehow interpreted such comments as a “threat,” but his pique must have been aroused by something more than the content of the comments. After all, he had heard similar remarks from the NECAMV. Perhaps Truman was upset by the tone of the comments as well as by the people who were delivering them. Clearly, Robeson and his associates did not represent the responsible brand of black leadership he found compatible in groups such as the NAACP.32

Nevertheless, Truman responded favorably to rising black activism, even though some of it came from elements he disliked. He kept in close touch with Attorney General Tom Clark about the Justice Department’s investigations of postwar lynchings. The department brought a federal indictment against Isaac Woodard’s assailant and tried him before an all-white South Carolina jury, which took a brief half hour to find him not guilty. The president and attorney general agreed that a case-by-case effort to prosecute racial violence was not enough and concluded that a national civil rights committee must be established not only to study lynching but also to explore solutions to a broad range of civil rights problems. By mid-October, Clark had drafted language for an executive order to create a civil rights committee.33 The president waited until early December to deliver the proclamation to work out some of the necessary details for its operations and perhaps to avoid any unnecessary political fallout before the November congressional elections. However, the voters elected a Republican majority to run the Eightieth Congress.

On December 5, Truman issued Executive Order 9808, creating the President’s Committee on Civil Rights (PCCR). Couching his language in Roosevelt’s wartime rhetoric, he declared: “Today, Freedom from Fear, and the democratic institutions which sustain it, are again under attack.” Rather than focusing solely on mob violence, he instructed the committee “to make recommendations with respect to adoption or establishment by legislation or otherwise of more adequate means and procedures for protection of civil rights of the people of the United States.”34

If in Truman’s political calculations the formation of the committee would satisfy his civil rights constituency without unduly angering the South, for the most part he was right. Most major black newspapers welcomed the executive order, and the Kansas City Call praised the committee’s establishment as “salutary and potentially of great value to the welfare of millions of Americans.” The southern press mostly ignored the executive order, and some even praised it for investigating the horrible crime of lynching.35 For the time being, the committee operated under the political radar.

PREVIOUS: Part V – Harry S. Truman

NEXT: Part VII – Committee Members

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes