TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART XIV: THE CIVIL RIGHTS REPORT AND TRUMAN’S LEGACY

Truman’s 1948 presidential victory did not provide the legislative mandate the president needed for his civil rights program to triumph. Below the surface little had changed in Congress. Democrats replaced Republicans as the majority party, but southern Democrats who gained from this triumph used their seniority to chair important committees and the filibuster to thwart whatever civil rights measures Truman sent them. Furthermore, Truman’s cold war concerns, particularly with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, helped disrupt the solidarity of civil rights advocates. To affirm ideological purity, liberal and labor groups, including the NAACP, the ACLU, and the CIO, purged their ranks of suspected Communists and left-wing associates. Many of the interracial bands of activists who had joined the Southern Conference for Human Welfare and the Henry Wallace presidential campaign to try to democratize the South suffered a blow during the Communist witch hunts, from which it was hard to recover. Anti-Communist liberals often played into the hands of conservatives, who used the fear of subversion to stop any civil rights reform whatsoever. The cold war did not halt the civil rights movement altogether; rather, it served to reduce the number of opportunities for change, particularly economic, and labor-related reforms that could be smeared with the red taint of communism.

Despite considering the cold war a more urgent priority, Truman did not stop pursuing racial justice. His administration had other weapons at its disposal to circumvent the obstructionist Congress, and the president quietly deployed them in a few notable instances. He approved the Justice Department’s filing of briefs on behalf of the NAACP and supported black plaintiffs in their efforts to overturn racially restrictive housing covenants. Many homeowners had placed these discriminatory stipulations in their deeds, which bound them to sell their property to whites only. Local courts had enforced them as legal contracts. The PCCR had received complaints about these restrictive agreements and recommended their elimination. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that the covenants could not be constitutionally implemented under the Fourteenth Amendment. In addition, over the next few years, Truman’s Justice Department joined with the NAACP to lodge judicial challenges to racial segregation in interstate transportation and public schools and colleges.95

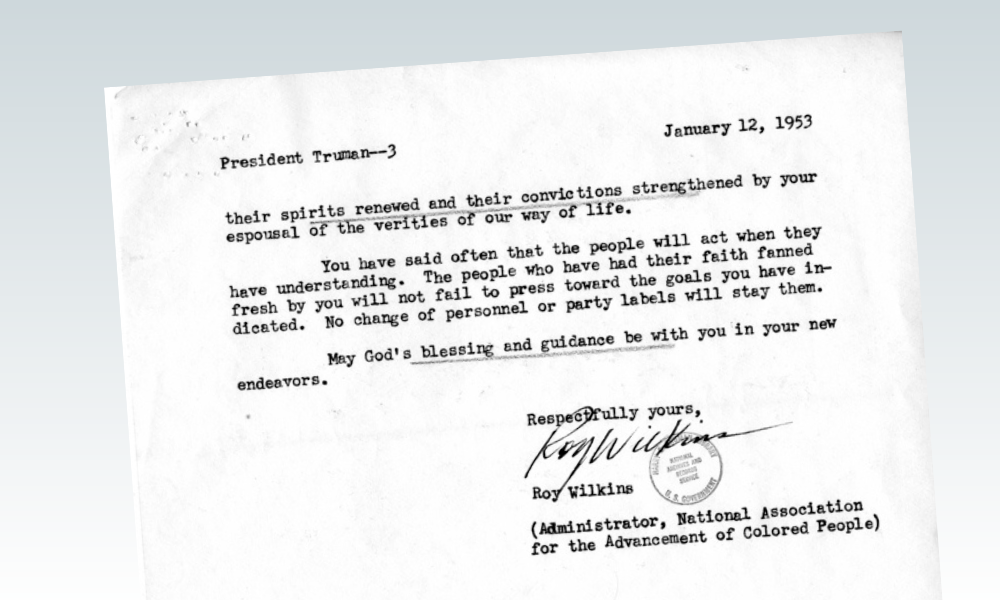

When Truman retired in 1953, he had accomplished more than any other president before him and most of those who came after him in establishing federal support for civil rights. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP wrote him that “no chief Executive in our history has spoken so plainly on this matter as yourself, or acted so forthrightly.96 Inspired by moral concerns and tempered by political reality, Truman lined up behind the concept of racial equality and helped thrust it on the public agenda.

From the archives of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library & Museum. Click here to view the full exchange.

Undeniably, human decency motivated him, but the president responded largely because the political landscape was changing significantly. Truman reacted to a rising social movement that a chief executive could no longer afford to ignore. Wartime and postwar ideology, diplomacy, and demographics had strengthened the position of African Americans seeking to eliminate white supremacy. There was nothing predestined to guarantee success; white Americans who held power, no matter how sensitive to their plight, would not take bold action unless black activists applied pressure and gained visibility at the national and international levels. This pattern became evident in the 1940s and would continue for two decades. Progress occurred in fits and starts, but as long as civil rights advocates, black and white alike, combined political power with appeals to moral conscience, the struggle for equality moved forward. Reports as forward-looking and eloquent as To Secure These Rights could not by themselves produce social change. Rhetoric and good intentions were not enough; it took power wielded by a determined mass movement and applied on sympathetic but cautious national officials to topple Jim Crow.

Harry S. Truman and A. Philip Randolph were still alive when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both men, as well as scores of anonymous black women and men, had helped provide the foundation upon which these twin legislative towers had been built. When civil rights forces sufficiently pressured the national government to fight on their side, both Randolph and Truman saw fulfilled much of what they had tried to accomplish in the 1940s. Over the years, Truman’s chief civil rights legacy remained the creation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights and its heralded report.

In some 176 pages, To Secure These Rights provided a detailed inventory of the civil wrongs done to African Americans and offered a road map for the country to follow to remedy them. Reading the report today, we should appreciate the insight of the committee at a time when segregation and disfranchisement reigned supreme. Yet more than half a century after publication of the report and four decades after passage of landmark civil rights acts, there remains a need to reflect on how the nation, now that it has secured fundamental civil rights for African Americans, intends finally to fulfill them.97

PREVIOUS: Part XIII – Truman’s Response and the Election of 1948

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes