TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART II: THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR II

Having largely avoided taking a firm stand on civil rights issues for nearly a decade, in 1941 Roosevelt faced a simmering confrontation that moved him off dead center. A. Philip Randolph, the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, threatened to mobilize 100,000 African Americans to march on Washington to protest racial segregation and discrimination in the armed forces and bias against blacks in the hiring practices of the federal government and defense industries. The historian John Hope Franklin recalled some of the prejudice blacks faced in the military. His college-educated brother, a high school principal, was drafted into the army and encountered a white sergeant who told him in no uncertain terms that he would “dedicate his years . . . to seeing that [Franklin] did nothing more exalting than peel potatoes.”4

With the United States on the threshold of entering World War II, Roosevelt preferred to avoid unfavorable publicity from a large demonstration of people protesting racial injustice in his own backyard. Urged on by Eleanor Roosevelt, the president met in June with Randolph and other civil rights leaders and subsequently issued an executive order creating a Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to investigate and publicize job discrimination. Randolph did not get a proclamation to abolish segregation in the military, but then again he had far fewer than 100,000 people to deliver to the nation’s capital. Despite the compromise, this incident suggested the rising power of African Americans to exert pressure on the federal government and foreshadowed tactics that would emerge more fully in the late 1950s and 1960s.5

Though the march on Washington did not materialize, blacks fought a “Double V” campaign to achieve victory against Fascism abroad and racism at home. In 1942, a group of Chicago pacifists organized the interracial Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and engaged in nonviolent sit-ins to integrate public accommodations in northern cities that continued to practice discrimination in spite of state laws that prohibited it. In 1943 and 1944, a group of female students at Howard University in Washington, D.C., one of the premier black institutions of higher learning, conducted sit-ins against cafeterias that barred blacks in the nation’s capital. Although these pathbreaking demonstrations did not spawn a wave of protests throughout the country, they did indicate the rising anger of African Americans about racial inequality and the expectation that they could do something to overturn it.6

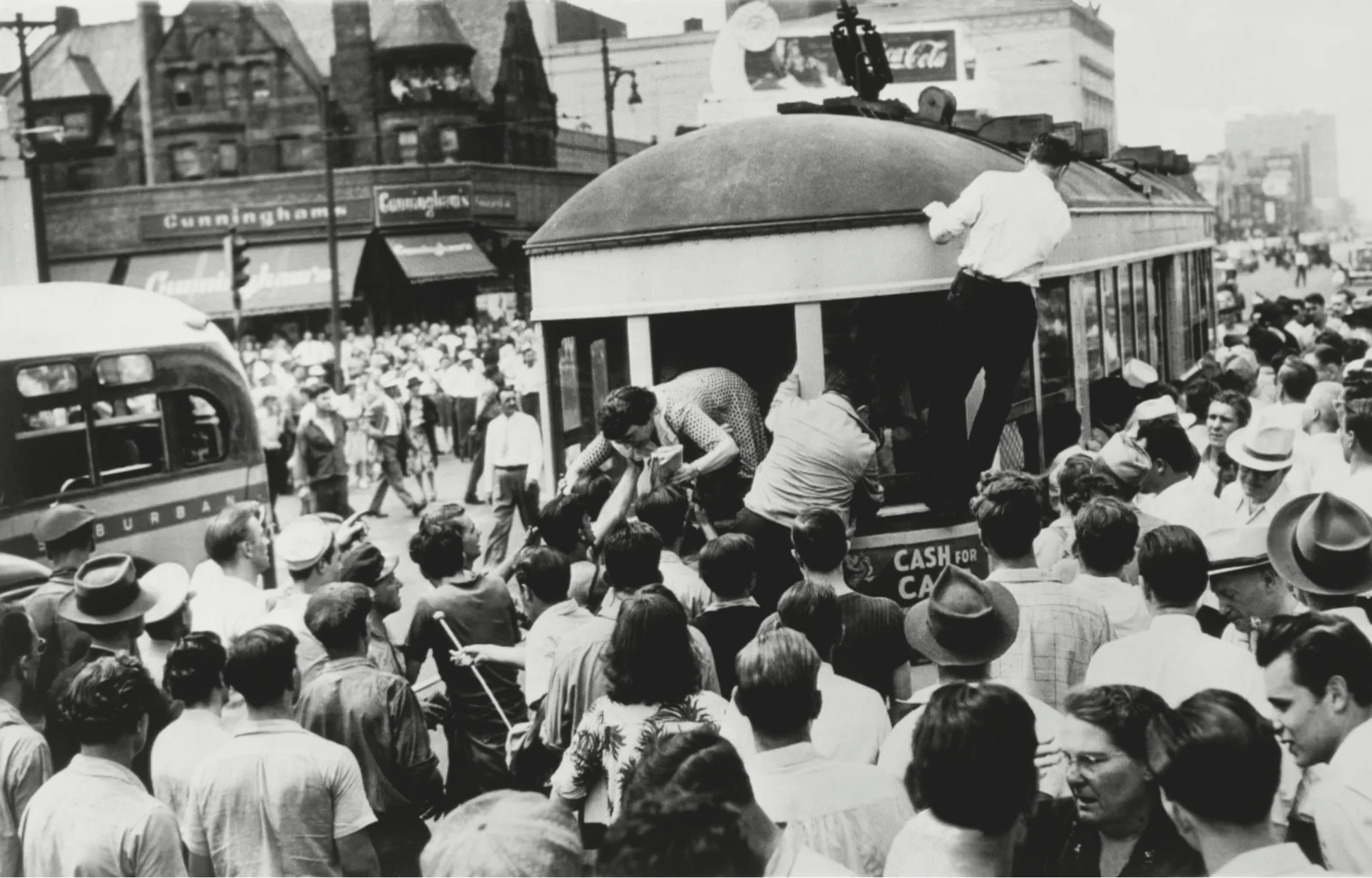

In 1943, anger spilled over into violence. More than 240 racial disturbances erupted in forty-eight cities around the country. Most of the problems stemmed from increasingly close contact between blacks and whites in transportation systems, recreational facilities, employment, and housing resulting from wartime migration within and outside the South and the stationing of black servicemen at southern military bases. Forced to compete for the short supply of affordable housing, crowded onto municipal buses, and in search of beaches and amusement parks where they could relax and forget their troubles, blacks and whites clashed while staking out their territory in contested public spaces. In Detroit alone, thirty-four people were killed, seven hundred injured, and $200 million in property destroyed. On the West Coast, where the population of African Americans had swelled by 33 percent during the war, fights broke out in Seattle, Portland, Oakland, and Los Angeles between blacks and whites.7

Passengers climb from rear of streetcar stopped by mob during race riots in Detroit, Michigan (June 22, 1943). Courtesy Library of Congress, photo LC-USZ62-132815

The war instilled in many African Americans an invigorated sense of pride and determination to reclaim their citizenship rights. If they could serve their country and risk dying for it, they deserved to be treated equally. Approximately a million African Americans, including 4,000 women, entered the armed forces, and about half were stationed overseas. The military taught them how to use weapons to fight the enemy and indoctrinated them in the wartime aim of crushing dictators who preached racist doctrines and trampled on democratic principles. African Americans took great pride in the elite group of soldiers that constituted the Tuskegee Airmen. The Airmen’s combat record in the air war over Europe was exemplary, and black pilots exhibited skills surpassed by none in fighting the Nazis. If Hitler’s Luftwaffe did not scare them, neither did racist white military commanders in the United States. At bases in Alabama, South Carolina, Michigan, and Indiana, black pilots staged demonstrations challenging their exclusion from or segregation in dining and recreational facilities at military posts.8

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, remained the leading organization challenging white supremacy. In 1944, the NAACP persuaded the Supreme Court to declare unconstitutional the white primary in a case from Texas, Smith V. Allwright. In the South, where the Democratic party had reigned supreme since the end of Reconstruction and Republicans were identified with the northern victors of the Civil War, winners of Democratic primary contests routinely triumphed at the general election. By preventing blacks from participating in these Democratic primary elections, whites deprived them of the only meaningful opportunity to cast a ballot in the South. Capping a twenty-year legal battle, the NAACP, led by its chief attorney, Thurgood Marshall, convinced the judiciary that the white Democratic primary in Texas denied African Americans the vote in violation of the Fifteenth Amendment. Because the rest of the southern states also employed Democratic white primaries, the decision in Smith v. Allwright had widespread impact. In 1944, approximately 5 percent of southern blacks were registered to vote; by 1948, the percentage had more than doubled.9 Additional legal challenges to racial discrimination in teacher salaries and segregation on interstate transportation systems not only succeeded in the courts but also accrued rich dividends for the NAACP in the astonishing growth of its wartime membership from 50,000 to 450,000.10

The war also encouraged white moderates and liberals in the South to attack racial discrimination. In 1944, a group of whites and blacks formed the Southern Regional Council (SRC) in Atlanta. The SRC functioned as an educational forum rather than an action group, but it supported efforts to expand the suffrage to blacks and poor whites.11 In addition, labor unions affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) conducted organizing drives to sign up white and black workers and achieved some success in Memphis, Tennessee, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina. These campaigns emphasized not only extending voting rights through abolition of the poll tax but also economic reforms that would increase the power and opportunity of workers to obtain a decent standard of living. Union halls became a place where blacks and whites could come together to initiate voter registration drives.12 Though southern white dissenters remained a definite minority and continued to face great obstacles, they had some reason to be encouraged that World War II had set in motion forces that would democratize the South.

Smith v. Allwright and the anti—poll tax campaign fostered voter registration drives that mobilized black women to participate alongside men. Because suffrage drives were often a community affair, women played a leading role as key members of churches, civic clubs, and professional associations. Shortly after the war, perhaps the best-organized effort occurred in Atlanta, Georgia. Though men gained most of the publicity and credit for its success in adding the names of 18,000 blacks to the voter rolls, female teachers and domestic workers joined together to ring door bells and conduct house-to-house canvassing of potential registrants. Narvie J. Harris, a black teacher, used the Parent-Teachers Association (PTA) chapter she had founded to help educate students as well as parents to the importance of the vote in achieving full citizenship. Atlanta’s black women, like their counterparts throughout the South, sought to extend the ballot chiefly to improve the conditions of their families and obtain jobs, health care, decent housing, and safer streets.13

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1938); Courtesy Library of Congress, photo LC-H21- C-820

Together with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, World War II helped reshape traditional thinking about the role of the federal government in promoting economic security and protection of basic civil rights. The antigovernment bias that had characterized Americans for much of their history diminished as the federal government used its considerable power to fight first the Great Depression and then the Second World War. In the process, groups that had suffered abuses at the hands of government, such as organized labor and African Americans, came to believe that Washington could protect their civil rights and civil liberties.14

PREVIOUS: Part I – The New Deal Coalition for Civil Rights

NEXT: Part III – Postwar Violence

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes