TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART V: HARRY S. TRUMAN

Upon taking office, President Harry S Truman immediately encountered an array of foreign and domestic problems that would have vexed FDR. Truman lacked his predecessor’s charisma, but he displayed greater sensitivity toward civil rights than had the more popular and experienced Roosevelt. Indeed, when Truman left the presidency in 1953, he had cemented the loyalty of black voters to the Democratic party and set the agenda for civil rights that guided the nation over the next two decades.

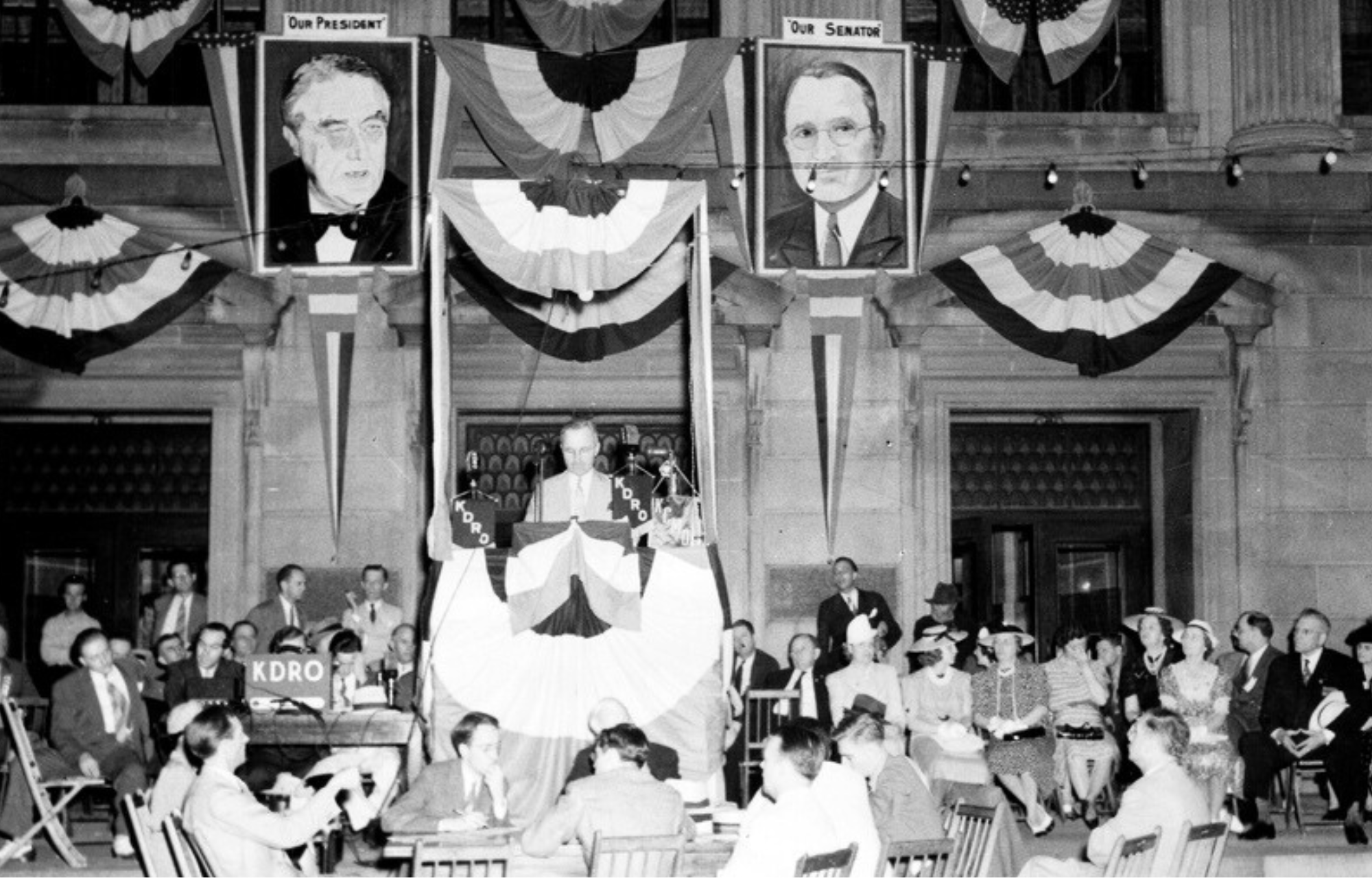

Truman’s role as a supporter of civil rights had not come easily. His Missouri ancestors had been slaveholders and supporters of the Confederacy, and his mother denounced Abraham Lincoln throughout her long life. Nevertheless, during the 1920s as Truman began his ascent into politics in his hometown of Independence, Missouri, he did not flinch from denouncing the revived Ku Klux Klan, which played an active role in electing candidates to office. Truman, who as a captain in World War I had led a unit largely made up of Irish Catholics, detested the Klan’s religious bigotry and intolerance. He moved up the political ladder by joining forces with the political machine run by the Kansas City boss, Tom Pendergast, who courted black votes and helped Truman get elected to the Senate in 1934. Running for reelection in 1940, Truman articulated his core principles as well as those that would gain wide currency in the approaching war. “I believe,” he declared in Sedalia, Missouri, “in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. In giving the Negroes the rights which are theirs we are only acting in accord with our own ideals of a true democracy.”20

Senator Harry S. Truman in Sedalia, Missouri during his Senate campaign. The July 1940 speech was broadcast by radio. Courtesy Truman Library, photo 58-707

Truman contended that the federal government had an obligation to use its power to eliminate obstacles to equal opportunity when state and local authorities refused to do so. By the time he became president in 1945, Truman had gone on record in support of legislation for a permanent Fair Employment Practice Committee, to extend voting rights, and to punish lynchers. Truman was not a reformer by temperament or vocation; rather, as a successful politician, he understood that he had to shape his convictions to meet the realities of the legislative arena. In this way, politics both constrained and constructed his vision. On the one hand, he encountered a Congress in which a conservative coalition of lawmakers had succeeded in blocking extension of the New Deal since the late 1930s. In the virtually one-party Democratic South, Democratic congressional incumbents had established seniority, which placed them in a position to chair important committees and to block reform legislation initiated by the president. On the other hand, Truman faced an electorate in which the strength of African Americans was expanding.

To resolve these political tensions, President Truman “recognized the trends and pressures and adjusted to them, sensing the need to maintain a rough equilibrium between shifting powers.”21 For example, he started out by continuing his commitment to the FEPC and then backed off. On November 21, 1945, the chief executive had a golden opportunity to give some meaningful enforcement power to the agency when the government took over Washington, D.C.’s Capital Transit Company during a crippling strike. However, he refused to authorize the FEPC to interfere with the company’s racially discriminatory practices. In response, Charles H. Houston, the former chief legal officer of the NAACP and a member of the FEPC, resigned in outrage.22

Truman also vacillated with respect to anti-poll-tax legislation. In early 1946, he endorsed the efforts of Congress to eliminate the poll tax. After the House passed a bill, he refrained from marshaling his forces in the Senate to rescue the measure from the clutches of die-hard southern enemies. In fact, Truman undercut reformers by declaring publicly that the states would have to work out the problem for themselves. Privately, he confided to one of the bill’s opponents: “There never was a law that could be enforced if the people didn’t want it enforced.”23 The president was undoubtedly correct about the dismal prospects of overcoming a filibuster, the Senate’s waging of endless debate, which required a two-thirds vote to shut off.24 Moreover, there were other vital problems of postwar economic reconversion and foreign policy that he had to address. Still, Truman, who believed that “the president can do nothing unless he is backed by public opinion, so far had not taken the opportunity to use his presidential resources to help educate the American people concerning civil rights.25

Furthermore, Truman’s sense of equality did not impel him to challenge segregation. The president asserted that his “appeal for equal economic and political rights for every American citizen had nothing at all to do with the personal or social relationships of individuals or the right of every person to choose his own associates.”26 In early 1947, Truman crossed a CORE picket line at Washington’s National Theatre that had been set up to protest the theater’s refusal to admit blacks. He believed that the primary problem with the formula of “separate but equal” was that the states accepted the first part of the equation but not the second.27 His moral convictions notwithstanding, the president, as the historian Barton Bernstein has commented, “shared the views of many decent men of his generation and thought that equality before the law could be achieved within the framework of `separate but equal.’”28

PREVIOUS: Part IV – Pressure for Reform

NEXT: Part VI – Creation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes