Guest Blog Post | November 28, 2018

The Pandit and the President

Marc Reyes is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. A Kansas City native, Marc’s research interests include U.S. foreign relations history and modern South Asia. Marc is a Fulbright-Nehru Fellow and will spend most of 2019 in India. His time there will assist him in completing his dissertation, a cultural and political history of India’s atomic energy and nuclear weapons programs.

Marc wrote the following guest blog post about Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s first visit to the U.S. in 1949 and President Truman’s reception of him.

A “…hero in his country’s fight for freedom.” The “political heir and spiritual son” of Mahatma Gandhi. “The most influential leader of Asia.” Such platitudes were common when describing India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Whatever description accompanied him, it was clear that he was more than the leader of Asia’s largest democracy. Pandit (a Sanskrit word and title befitting a Hindu scholar) Nehru’s advocacy for the nonaligned nations movement and post-WWII decolonization gave him international stature, someone who belonged to the world, not just his fellow Indians.

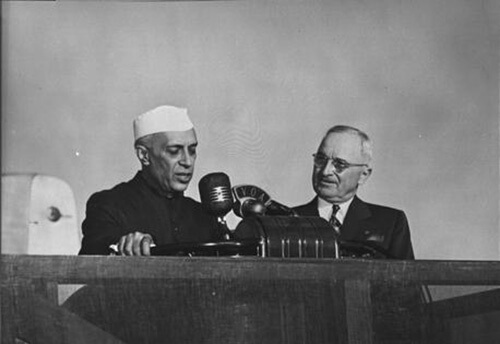

Prime Minister Nehru of India replies to President Truman’s words of welcome.

As the Indian head of state, Prime Minister Nehru traveled to many nations, but on October 11, 1949, he arrived in a place he had never visited – the United States. Flying in from London, aboard President Truman’s personal plane The Independence, Nehru arrived in Washington, D.C. on a cloudless, unseasonably warm autumn afternoon. As Nehru exited The Independence, he found a smiling Harry Truman, who gripped him by the hand and welcomed the Pandit as “the loved and respected leader of a great nation of free people.”

Departing for the city, Prime Minister Nehru waves to the crowd.

The welcome party included the Secretaries of State, Defense, and Agriculture as well as an honor guard who greeted Nehru with a nineteen-gun salute. Adding to the sounds of the ceremony, the U.S. Army Band serenaded Nehru with the Indian national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana.” The festivities marked the beginning of Nehru’s three-and-a-half week visit to the United States where he would hop from metropolises (Chicago and New York) to the countryside (the Tennessee Valley and Mount Vernon) to gravesites and memorials (FDR’s grave and The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier).

Prime Minister Nehru, with President Truman, inspects Honor Guard.

At more celebratory stops, Nehru relished his role as advocate for his fledgling country. He needed to return home with commitments of badly needed food aid. Nehru’s 1949 U.S. visit arrived as India feared yet another deadly famine. Only six years earlier, the Bengal famine took between two and three million Indian lives. Even before the 1947 independence, famine relief was already a hot topic of conversation between the U.S. and India. At a United Nations meeting held the previous year, President Truman met with an Indian colonial delegation where diplomats made the case for two million tons of surplus grain.

Whether colony or free, President Truman recognized the importance of India and kept a close eye on national developments. When India emerged as a new nation, the President issued a statement celebrating “India’s new and enhanced status in the world community of sovereign independent nations.” When an assassin’s bullet ended the life of Mohandas Gandhi, Nehru’s mentor, in early 1948, Truman lamented that Gandhi’s death was not just a loss for India but the entire world. Truman added that, “Another giant among men has fallen in the cause of brotherhood and peace.” India and its leader were certainly on the mind of President Truman and his top national security advisors in the fall of 1949. Nehru’s U.S. visit came less than two weeks after the Chinese Communist Party came to power. To Truman and his administration, India emerged as a possible democratic and capitalist counterweight to communist China, and a senior administration official described Nehru as the “most vital and influential person” for U.S. objectives in Asia.

President Truman greets Prime Minister Nehru as he exits The Independence.

For a visit packed with banquets, keynotes, and honorary degrees, what seemed to animate Nehru the most during his U.S. visit were events outside official Washington, when he met with everyday Americans. During his trip, Nehru met his share of bankers and businessmen in New York or academics in Boston, but it was his stops in the American heartland that left him hopeful for India’s future. One such example was when Nehru and his delegation, including his daughter, the future Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, visited farms in Illinois’s Fox River Valley. The Pandit toured three family farms and was surprised to learn about gas-powered stoves, mechanical corn pickers, and milking machines. So much of farm labor in India was still done by hand. In the U.S., Nehru witnessed how technology made farm tasks quicker and easier. With machines, more food could be grown and brought to market sooner. These advancements fueled Nehru’s already healthy fascination with technology and the ways it could improve human life. But most of all, he enjoyed conversing with the families behind the farms and how their work bettered their lives and communities. One of his hosts recalled how happy ringing the dinner bell made him and at this stop, he discovered the wonder that is pan-fried chicken.

Prime Minister Nehru examines corn grown on an Illinois farm.

After three and a half weeks, covering nearly ten thousand miles, Prime Minister Nehru reached the end of his U.S. visit and returned home. The Times of India newspaper described Nehru as relaxed while in America, comfortable talking to anyone, whether congressman or citizen. The paper believed that the U.S. leadership was impressed with independent India’s first head of state. Nehru informed his hosts of his deep gratitude for their hospitality and that everywhere he went he encountered friendly people. He ended his departing statement by proclaiming that his visit had led to a stronger understanding between the two countries.

The mechanisms of a farm tractor are explained to Prime Minister Nehru.

Proving that his words were more than a boast, by 1951, the U.S. and India had struck a loan deal, which helped India purchase two million tons of wheat. The following year the two countries signed a technical assistance agreement. Point Four dollars started rolling into India for community development projects aimed at modernizing India’s half a million rural villages. President Truman had described Nehru’s visit as a “voyage of discovery” and that when he departed, the U.S. and India would see each other as “warm friends.” Both nations found common ground especially on the issue of hunger and famine relief. This understanding was crucial as the United States sought to better understand the developing world and initiated a nearly two-decade-long program of U.S. assistance – development grants, loans, food aid, increased trade, technical expertise – to India that would boost economic growth and yield higher Indian agricultural outputs. That progress had many steps, some forward and some backward, but the relationship fundamentally changed when Nehru exited The Independence and found a smiling President Truman, eager to meet him and start a new chapter in U.S.-Indian relations.

Join our email list to receive event updates and the latest Truman news right in your inbox: