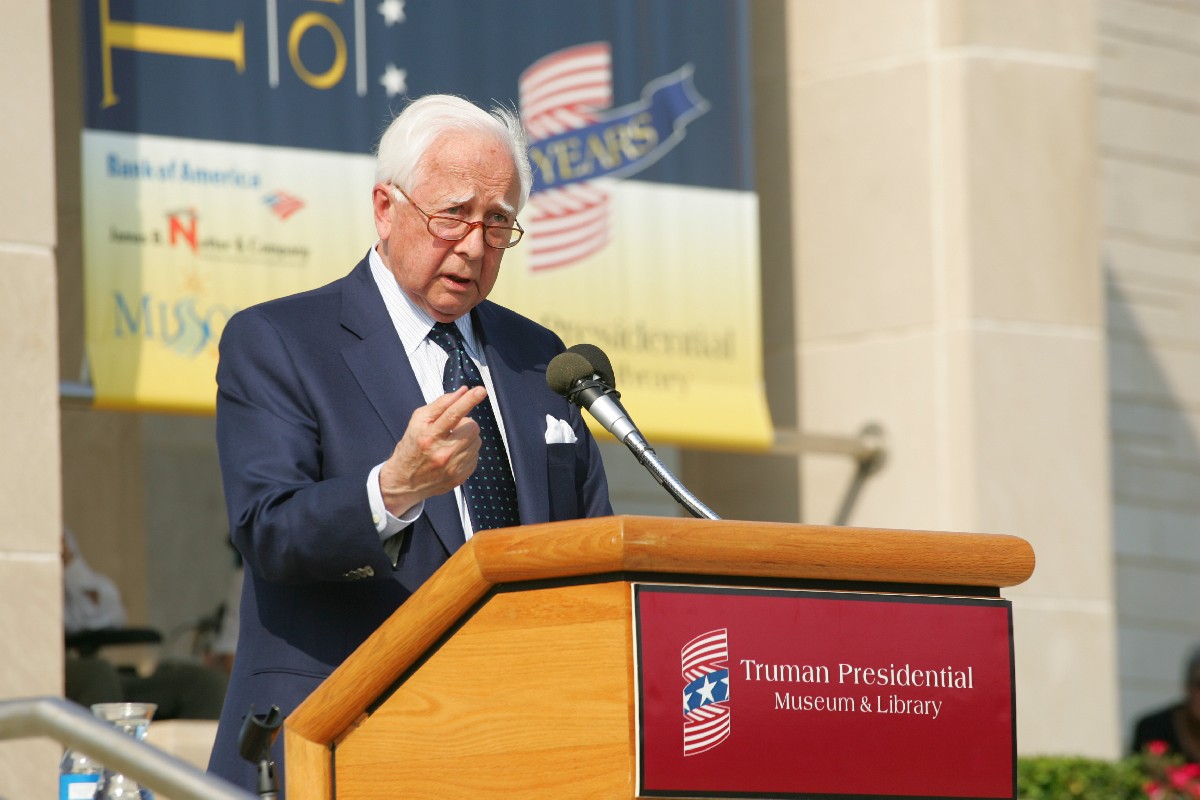

David McCullough on Truman, Presidential Libraries and Education | August 8, 2022

On June 13, 2007, David McCullough, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Truman, returned to Independence, Missouri and the Truman Library to deliver a keynote address marking the 50th anniversary of the Library’s dedication in 1957. The transcript of his address follows.

What a pleasure it is to be back here and what a lot I learned in the 10 years that I worked here. A time that flew! And my heart is still very much in Jackson County wherever I am, and to be welcomed – as I have been by so many people even before I arrived at the Library this afternoon –has been a great kick… people stopping when I was out walking in the street. Just this morning one very friendly, nice lady came up and greeted me and she said, “Welcome back, how good to see you here Mr. Cronkite.” (Laughter)

I want to talk today about presidential libraries, but I really want to talk mainly about education.

The legacies of Harry Truman are manifold and it would take another shelf of books the size of my own biography of Mr. Truman to adequately measure all that. He himself was a great student of history which is extremely important to understand if one wants to understand him. And he understood one of the manifold lessons of history is that you have to wait a while to pass judgment. You have to wait for the dust to settle. He said it took 50 years before you could fairly estimate, judge, appraise the performance of a president or anyone else. And so it’s now been 50 years and here we are.

The Truman Library at 50

The 50 years during which this Institution has held its doors open have been everything that Mr. Truman could have hoped for. And that day, July 6, 1957, was for him one of the great days of his life, as he said. In fact, 1957 was, fulfilled all the dreams that he had for what he hoped would happen in the years of his post-presidency, a grandson was born on June 5, Clifton Truman Daniel, and the library opened on July 6.

It was a big occasion, as it should have been; the guests included former President Hoover, Eleanor Roosevelt, Speaker Sam Rayburn from Texas, four sitting senators, nine governors, and the Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren, and Dean Acheson, his former Secretary of State. Truman was very excited. In the days just before, he wrote to Acheson, “I’ll be knee deep in big shots.”

Earl Warren, who was the keynote speaker, the main speaker, said quite rightly that the Library itself was a milestone in American history. It was the first presidential library to be developed while the president was still alive. The FDR Library preceded it, but Franklin Roosevelt was no longer present. President Hoover, who of course preceded Harry Truman, would also have a presidential library and all together 12 of our presidents have Presidential Libraries beginning with President Hoover.

An Advocate for America’s Presidential Libraries

The Presidential Library System is very much in the news and very much a subject of serious controversy. Just the day before yesterday in New York, a friend of mine said, “hasn’t this Presidential Library thing gotten out of hand, why do we need all of these Presidential Libraries all over the country. Why can’t they all be in Washington under one roof?”

Well, I would like to answer that question in a public way.

The Presidential Library System works and it works in many ways that ought to be clearly understood. Part of the value of coming to a presidential library is that you come to the place where the president came from. You come to the place that helped create that person, that personality, where he evolved. When I first told my editors I wanted to write about Harry Truman, I said I wanted to write about a very different kind of America and a very different kind of American from the Roosevelts with whom I had been working with my book on Theodore Roosevelt. I wanted to come to Independence. I wanted to be here, stay here, soak it up. That’s of the utmost value to all who come to use the library: students, scholars, and the rest.

And there’s a second reason why it is so important and that is the staff. We mustn’t just think that the great collections here are the ultimate value, they are, of course, of infinite value, but the staff too is of the greatest possible importance. Mr. Devine mentioned Liz Safly, wonderful Liz Safly, whose help for me and so many was invaluable, but also because she introduces people to others who live in the community. And through Liz, I got to meet some of those that were able to open windows for me, open doors for me, give me insights into Mr. Truman’s life and his place in this community that I would have missed entirely had it not been for Liz or had I been doing the research in an archival building in Washington D.C.

People like Dennis Bilger, Erwin Mueller, and Dr. Benedict Zobrist, who was the director of the library then, people that I worked with who were there because they were there also working on projects like Professor Robert Ferrell from Indiana, and the people that Liz introduced me to in Independence, most particularly Sue Gentry. Sue Gentry was a volume that was a library unto herself of life in Independence as she had seen it from her childhood, living just a few houses away from the Truman’s and as a reporter for the paper here. And Lyman Fields, wonderful Lyman Fields of Kansas City, who again opened doors for me, did me favors, became my friend, lifelong friend. And he and Liz, he and Liz and Sue were… I can’t possibly express how important they were to my understanding of Mr. Truman and to my enjoyment of the experience of working here. The time flew.

So don’t just think of this as a great place to come and see archival treasures; it is that, it is that to a degree beyond what most people understand. It’s also a place where the human side of it is of infinite value to scholarship, to education, to learning.

Now, Harry Truman put Jackson County on the map and this library keeps him on the map. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that this library is a national treasure. It is also, of course, a great addition to the civic cultural amenities of Kansas City and its environs. It’s as important as the art museum, it’s as important as the new wing of the arts museum, which I had the pleasure to visit yesterday, and the upcoming arts center that’s to be built. It ought to be seen as part of that, because history isn’t just about politics and the military, and social issues, history is also about art and music and the theatre and the world of the spirit and literature and poetry, as Harry Truman understood perfectly.

My feeling for libraries is really so deep and so, and so, difficult to express that I sometimes find myself without the words to say what I feel. I feel that way about public libraries, university libraries, and our Presidential Libraries. Don’t ever think our Presidential Libraries aren’t worth everything that has been put into them, and then some, and the fact that they are spreading out to so many different locales in the country is wonderful. It’s bringing history out into every part of our nation and that is very important for the education of our children and our grandchildren.

History Education: A Vital Mission

A short while back I was… I finished up a talk on a college campus in California and it came time for the question-and-answer session and I was asked, “Aside from Harry Truman and John Adams, how many other presidents have you interviewed?” Well, appearances not withstanding, I never knew Mr. Truman and I never knew Mr. Adams.

I did see Harry Truman once. It was in 1956 and I had just started my first job in New York and my wife, Rosalee, and I had moved into our first apartment together in Brooklyn Heights and we were starry eyed about being in New York and having a job and the excitement all around us. And one night coming home, coming up out of the subway station near our apartment, which was in the basement of the old St. George Hotel in Brooklyn, there was a little crowd gathered and I asked what was going on and they said the governors coming, Averill Harriman. Well, I had never seen a governor before in my life so I waited and sure enough up came a big car and out of the back seat stepped Averill Harriman looking very tall and very handsome and then right behind him came former President Truman and he was right there, right beside me and I’ve often been asked, well what do remember about him? Well, what I remember was that he was in color! We didn’t have color television, we didn’t have color photographs and newspapers and he had very strong healthy color, high color, ruddy, very blue eyes, greatly exaggerated by his thick glasses. And he didn’t look like a little fellow from Missouri to me at all, he looked like a giant.

I had the thrill that goes with seeing somebody of such importance at a very early age and I have never never forgotten it. I think now how wonderful it would be if I could go back in time and reach out and just tap him on the arm and say, “Mr. President, some day I am going to write a book about you.” John Adams and Harry Truman have much in common, both were farmer’s sons, both were preceded and followed by taller, more glamorous, charismatic Presidents; Washington and Jefferson, before and after Adams, Roosevelt and Eisenhower, before and after Truman. Neither of them was ever thought to be charismatic and neither of them was ever afraid of anything. Neither of them ever failed to answer the call of their country to serve, never. Both of them believed fervently in the importance of education, both of them were avid readers all of their lives, and both of them wrote wonderful letters all of their lives and kept diaries. And it is through those letters, those marvelous letters, that one can really get to know them, get to know them in many ways better than you can know people in your own real life. For one thing, in real life, we don’t get to read other people’s mail. And, of course, today almost no one writes letters and very few in public life will ever keep a diary ever again.

The treasures of this library include those letters that Harry Truman wrote back to Bess Wallace during World War I, for example. The wonderful letters he wrote before he became somebody in history. If we had nothing but the letters that Truman wrote, the recollections of his friends, about his life before he became a national figure, if that’s all he had done and those letters had been discovered somewhere, they would be of the utmost importance because they give us a window on his life, the way of life, his times, what he went through, the enormous arc of experience of that generation that surpasses almost any single record done by someone at that time.

We know what it was like to work on a farm, we know what it was like to fail in the haberdashery business, we know what it was like to struggle as a county judge or county commissioner here in Jackson County, what he was worried about, what he was ambitious to achieve in his life and, make no mistake, ambition is part of it, it’s all through what Adams wrote and what Abigail wrote to him, for him. One of the most vivid scenes in the whole story of John Adams happened late in his life in the last year of his life, 1825, when young Ralph Waldo Emerson came to call on John Adams at his home in Quincy. What a scene, what I’d give to have been an eyewitness or a fly on the wall to that scene. These two extraordinary Americans, two quintessential New Englanders, talking, expressing themselves. Fortunately, Emerson recorded much of what was said and one of the things that was said was by Adams who at one point said, “I would to God that there were more ambition in the country. And then he paused and said, by that I mean ambition of the laudable kind, ambition to excel.”

Read to Lead

That same theme, the ambition to excel, to serve, runs through all of Harry Truman’s life as does the love of books and reading. In the Boston Public Library, there are 3,802 books that belong to John Adams who purchased those books at a time when books were extremely expensive, and who was a man like Harry Truman, who never had any personal wealth to speak of whatsoever so we know right away how much those books meant to him. We know right away which books he purchased. What he was reading.

And one of the points I would like to make today, and I hope I can be as clear as possible, is that we are what we read. There was a very popular book some years back called we are what we eat, which, of course, is true, but we’re also what we read. What was John Adams reading? Well, the first book he ever bought with his own money was a small volume about that big of Cicero in Latin. He was 14-years-old and there is no question that he was extremely proud that he at last owned a book; we know that because he wrote his name in it six times. Harry Truman was given a set of Plutarch’s Lives by his father as a boy.

How important it is to know that. How important it is to know that he read Shakespeare and Plutarch just as John Adams did. And that he read Latin for pleasure even in his adult years. Nobody who was recovering Washington in the days of President Truman ever knew that. Or ever thought to ask him, “What do you read Mr. President? What do you read for pleasure?” Wouldn’t it have shattered all the stereotype pictures of this so-called backwoods hick, small time machine politician from Missouri to understand that he read Latin for pleasure, including Cicero?

Truman’s teachers have left a record in this library of what they observed of young Harry Truman. Truman’s teachers are of the utmost importance in the story of President Harry S. Truman because teachers are the most important people in our society. We talk about V.I.P.s, very important people, we ought to talk about the M.I.P.s, the most important people, the teachers. And, we must get over the idea that they are sort of glorified babysitters who look after our children and grandchildren while we do what counts in society. They are doing what counts because what they do counts in the long run which is of course what history is about.

Harry Truman, as you probably know, is the only president of the 20th and 21st centuries who never went to college, but that statement shouldn’t end there. He also received a better education in the high school here in Independence then most students receive in colleges today. For one thing, he was required to take Latin; it was required to take history.

Do you know that in the 50 top rated colleges and universities in the country today it is possible to graduate with a degree from those institutions having had no history whatsoever, none? Do you know how deplorably bad is the understanding of the story of our country on the part of our children and grandchildren? Do you realize, are you aware, that we are raising a generation, we’ve been raising several generations, for the last 25 years of young Americans who are by and large historically illiterate?

It has got to stop, we have to fix it, we can fix it, and that, to a large degree, is the most important part that this Library and the Presidential Library System can perform for our society, for our country.

Ethel Noland who was Harry Truman’s cousin, wrote some very perceptive things about Truman, she said among other things, “I don’t know anybody in the world who ever read as much or as constantly as he did. He was what you would call a bookworm. History became a passion as he worked his way through a shelf of standard works on Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.” “He had a real feeling for history,” she wrote, “that it wasn’t something in a book, that it was a part of life, a section of life or a former time. That it was of interest because it had to do with people.” Harry Truman understood that history is human, he understood that history isn’t simple, that the history of our country isn’t simple. America isn’t simple. He understood that in a way, there is no such thing as the past, nothing ever happened in the past, it only happened in the present, someone else’s present, not ours.

John Adams, George Washington, Harry Truman, they didn’t walk around saying, “isn’t this fascinating living in the past; aren’t we remarkable in our funny clothes.” Truman understood the English language.

Look at the famous speeches of the 1948 campaign. Almost all delivered extemporaneously from the back of the train. Look at the quality of the language, the good clear English language. How proud his teachers must have been. If a one-syllable word would suffice for a three-syllable word, you could count on Harry Truman to use the short word, just as Abraham Lincoln did. And it had much to do with the fact that he’d had Latin. He’d had a classical education which is exactly the kind of education that John Adams had or Thomas Jefferson, and if you were George Washington or Henry Knox or the General Nathaniel Green and you’d only had a 6th grade education, then you read the classics in English translations. The classical education was what they understood history to mean in the founding time. There was no American history to read so they read classical history and from classical history came their notions of honor, virtue, honesty, character.

The Education of Harry Truman

Character is destiny the Greeks said and if you want to study that in a living model look at the story of Harry Truman. Common sense, common sense isn’t common, as Voltaire observed, and who knows how many before Voltaire. Truman understood that: the enormous value, bedrock value, of common sense.

Now, who were those teachers? Tillie Brown, Matilda Brown, who taught English, Margaret Phelps who taught History, Ardelia Hardin who was the Latin teacher. It was quite a trio and, in my view, there ought to be a statue here in Independence, maybe over in the Square, of those three teachers and what they stood for, not just because they were Harry Truman’s teachers, but what they stood for: the old American dream of education for all, which began with John Adams’s Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the oldest written constitution still in use in the world today. Preceded our own national constitution by ten years in which Adams wrote, “it shall be the duty of the government to educate everybody” and then he spelled out what education should mean, in effect as a good 18th century man, he indicated that education should be about everything: arts, science, literature, finance, architecture, natural history, and about honesty and integrity and generosity.

We discussed today whether we should be educating our children in values, teaching values in the public school, of course we should, certainly if we wish to follow the dream of the founders.

Harry Truman was exactly the kind of man to rise in public service as the founders dreamed of. Not a creature of privilege and wealth, not the creation of the media, not false, not self-serving, but a farmer’s son who had had the blessing of education in a free society where we are free to think for ourselves.

Tillie Brown, who in many ways is the one that I admire particularly because she was the English teacher, kept some of the composition books, or the composition books have survived from his time with her. His little school book compositions in her class. Here’s some of what he wrote, “The virtue I call courage is not in always facing of the foe but in taking care of those at home. A true heart, a strong mind, and a great deal of courage and I think a man will get through the world.” Notice, he puts heart ahead of mind.

Ardelia Hardin, the Latin teacher, said later that it was the boy’s steadfastness that most impressed his teachers at that age. And Margaret Phelps on history, “it cultivates every faculty of the mind,” she wrote, this is a high school teacher back at the turn of the century, “it enlarges sympathies, liberalizes thought and feeling, furnishes and approves the highest standards of character,” character again and again coming through what they wrote.

When Truman appointed George Marshall Secretary of State, General Marshall held a press conference at which, during which, he was asked at one point if he had had a good education at V.M.I., Virginia Military Institute, and he said no, and he was asked why. He said because we had no history.

Falling Short: The Teaching of American History

Not long ago, I was teaching a course, a seminar for a week at one of our finest universities, an Ivy League university. I had 25 students, all seniors, all history majors, all honor students. In other words, the cream of the cream of the crop. The first morning, to get things started I said, “how many of you know who George C. Marshall was?” Not one, not one. Finally, after an extremely embarrassing silence, one boy said, “did he maybe have something to do with the Marshall Plan” and I said, “well we’re off and running.”

Just earlier this week, this will be hard for you to believe, it stunned me so I felt like I had been hit by something. Rosalee and I were having lunch at a little café lunch counter on a main street in a small town in Connecticut. Family-owned business, Greek mother and father, children working there in the restaurant and the oldest of them, a very attractive young woman, college student, sat down to chat with us, and Rosalee said to her that I was the author of the book about John Adams and she nodded and Rosalee said, “you know who he was don’t you?” And she said no. And so then, I said, “Well, do you know who the first president of the United States was?” No. She’s in college. She speaks three languages: English, Greek, and Spanish, perfectly. She is a whiz on the computer and she didn’t know that George Washington was the first president of the United States.

A recent study done by the council of the American Alumni in Washington, a non-profit organization revealed that the level of understanding of American history among college students in the top 50 universities and colleges in the country is below what it used to be in high school 25 years ago. Question 19, who was the commanding American general at the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown? Most of them said it was Ulysses S. Grant. Washington did come in second; Douglas MacArthur came in third.

I wonder what Truman would have made of that. We’ve got to make some changes. Very quickly, we’ve got to help the teachers more. We’ve got to help the aspiring teachers more by giving them the right kind of education. We’ve got to stop graduating young people with degrees in education and no major in a real subject because you can’t teach a subject you don’t know very effectively because not knowing it makes it more difficult, to be sure, but also because you can’t love something you don’t know any more than you can love someone you don’t know.

We all know that the great teachers are those teaching a subject that they love. We have all been lucky enough, I think, to have such teachers. Just like Harry Truman’s teachers. Come over here and look in this microscope, you’re gonna get a kick out of this. Here is a book that’s not on the reading list; take it home over the weekend, it’s not required but I think you’ll like it. Come on in early tomorrow morning and I will explain your question in more detail. I don’t mind coming in if you’ll be here. We’ve all had teachers like that. They can throw open the window for us.

In my years in college, I was required to take two terms of history; as an English major, I was still required to take two terms of history. I took a course in European history and there was a discussion group taught by a graduate student. All I remember about him was that he was from the South. And one morning, early in the new term, he said to us in the discussion group, “I don’t want you to spend a lot of time memorizing dates and quotations. I am not going to grade you on that. That’s what books are for, you can look those things up. It is much more important for you to understand what happened.” Well, for me, it was as if he had thrown open a window and let in fresh air from the mountains. It was as if I could have gone to the window and flown. It was thrilling. It changed my life.

“Give them more sense of what their lives are worth”

Last year, I went to speak at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and at a dinner the evening of the speech I was seated next to Dr. John Hubbard, the former president of USC who is a historian of the British in India. He’s 90 years old or thereabouts. Wonderful, educated, charming man, and I was talking about my time in college and I told him that story and how it had changed my life and he looked me right in the eye and said, “That was me.” He was the graduate student. So, I had the chance to thank him. I wouldn’t have missed that for anything in life.

I want to read to you something that Dean Acheson wrote before Truman went to Yale to be a fellow at Yale, to be a guest of the University, to live there and stay there and associate with the students in 1958. Dean Acheson was an extremely wise man and learned and, like Harry Truman, he knew how much more there was then met the eye about people. He saw beyond the surface manifestations of Harry Truman or what the press described him as, just as Harry Truman could see beyond this elegant, Edwardian-looking Dean Acheson who seemed to many so stuffy and unapproachable. They became very close friends and their exchange of letters in Truman’s post presidential years is one of the great treasures of the Truman Library; wonderful letters, so expressive, so uplifting in so many ways. And here’s what Dean Acheson wrote to a member of the Yale Corporation, as he was a member of the Yale Corporation, to Professor Thomas Bergan, who would be Truman’s host:

“Mr. Truman is deeply interested and very good with the young. His point of view is fresh, eager, confident. He has learned the hard way, but he has learned a lot. He believes in his fellow man and he believes that with will, courage, and some intelligence that the future is manageable. This is good for undergraduates; he is easy, informal, pungent. He should not be asked to do lectures for publication; the pressures on him are too great. It is not his field. It is not what he says, but what he is which is important to young men and this gets communicated. I should want Mr. Truman to be received at Yale with honor and with simplicity. Not as a show, not with controversy, not as a lecturer in a field, which I do not believe is yet a discipline, political theory or science, but as one who could, if in some way be wired for spirit, give our undergraduates more sense of what their lives are worth.”

No one who comes to this library, no one who works in this library, who has the privilege of learning from the great collections here, working with the staff can fail not to be wired with the spirit of Harry Truman.

Truman never, ever lost faith in education. Truman never, ever wavered in his faith in education. Neither should we.